HOT, WET AND OUT OF CONTROL:

The history of Texas’s power struggle with water.

Commissioned for Topic's Federal Project No. 2, Re-examining America.

Special Thanks to my editors Topic Joanna Lehan, Caroline Smith, Michelle Legro, and Andrew Sansom from The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, and Jason Reed for West Texas expertise, My uncle David Farris for helping me find our family homestead in Shallowater and Ann Pizer for countless edits and handwringing sessions.

In my native state of Texas, prosperity hinges on extracting oil and natural gas from subterranean reserves formed millennia ago. The same goes for water, which, like oil and gas, is in limited supply; there’s only so much of it to go around. To make matters worse, the water we do have is unevenly distributed. In East Texas, moisture and storms entering from the Gulf of Mexico saturate the humid and swampy landscape. As you move north and west, the climate becomes dry to the point of being parched.

Texas is a place of extremes. Over just two days in August 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped 51 inches—about a year’s worth of rain—on East Texas. The state is also a place of intense heat, where temperatures can soar above 100 degrees for weeks in the summer. The land is prone to both drought and flooding: Houston is routinely inundated with floods and storms of ever-increasing ferocity, while Dallas, to the north, almost ran out of drinking water during a seven-year dry spell in the 1950s, which Texans reverently call the “drought of record.” According to the National Integrated Drought Information System, approximately 13,612,000 Texans are currently living in drought conditions, the worst of which are concentrated in North and West Texas.

How to manage the magic of water has been an elusive question for quite some time in Texas. In 1861, in an attempt to mitigate the effects of flood and drought and figure out how to assign water rights among competing landowners and municipalities, the Ohio Supreme Court case Frazier v. Brown deemed groundwater “so secret, occult, and concealed … an attempt to administer any set of legal rules in respect to them would be involved in hopeless uncertainty, and would be, therefore, practically impossible.” Using this rationale—and in the absence of any real regulation—the “rule of capture” has become the only law governing water rights in Texas. In other words, a landowner’s right to water is only dictated by the power of their pump to swallow it. This capricious legal system, or lack thereof, also accounts for the fact that all the water in Texas is already spoken for. In fact, Texans have been legally granted more rights to water than actually exists.

![Fishing on the Texas Colorado River in Austin.]()

How to manage the magic of water has been an elusive question for quite some time in Texas. In 1861, in an attempt to mitigate the effects of flood and drought and figure out how to assign water rights among competing landowners and municipalities, the Ohio Supreme Court case Frazier v. Brown deemed groundwater “so secret, occult, and concealed … an attempt to administer any set of legal rules in respect to them would be involved in hopeless uncertainty, and would be, therefore, practically impossible.” Using this rationale—and in the absence of any real regulation—the “rule of capture” has become the only law governing water rights in Texas. In other words, a landowner’s right to water is only dictated by the power of their pump to swallow it. This capricious legal system, or lack thereof, also accounts for the fact that all the water in Texas is already spoken for. In fact, Texans have been legally granted more rights to water than actually exists.

In John Graves’s erudite and melancholy 1960 memoir, Goodbye to a River—a regional classic—the Texas native chronicles his canoe voyage with his dachshund down the Brazos River, which begins in North Texas and runs to the Gulf of Mexico. The book was a cri de coeur of sorts: Graves had taken the three-week canoe trip because he was concerned that the river’s beauty would be ruined by the planned construction of nine dams along its 1,200-mile path.

In May, I set out in search of aqueous plenty and scarcity. Inspired by Graves’s efforts, but forgoing a young pup in favor of my camera, I decided to embark on a 400-mile picture-making journey from Central Texas to the site of my ancestral home in the aptly named town of Shallowater, located in the dry northwestern part of the state known as the Panhandle. I wanted to craft my own meandering story of Texas water.

I dowse with a digital camera. The light captured and reflected from my subjects is converted into an electric charge that is then measured and turned into a series of numbers expressed as code. In turn, these numbers and symbols are translated again to create the pixels on the screen that you and I perceive as a photograph. At the code level, I often rearrange the light contained in those characters to inject aberrant rivulets of pixels into my images. These distortions come from the file itself and hint at the many possibilities that reside in the depiction of a given subject, while revealing the potential of photographs left untaken.

This process is especially apt for depicting the protean nature of water, which is one of the few substances on our planet that exists commonly as a gas, solid, and liquid. The inclusion of altered pictures renders the straight images I choose all the more surreal, and further embraces the capricious nature of what artist Jeff Wall has called photography’s “liquid intelligence.”

I began at Mansfield Dam, just a few miles outside of what I consider Austin proper. Constructed between 1937 and 1941 as part of the WPA, Mansfield Dam was originally built to contain the floodwaters that had previously devastated the Austin area. The dam forms one of the six Texas Highland Lakes on the lower Colorado River; they provide both drinking water for the greater Austin area and recreational opportunities such as boating and waterskiing. When it was built, it appeared to have been constructed in a desert. Today, people can scuba dive in what was once a desolate valley.

From there I drove to Llano, Texas, an hour northwest of Austin—a town whose eponymous river cuts through its center. A small dam creates a lake on the west side of the Roy B. Inks Bridge, which bisects the town. East of the bridge, the river meanders to a trickle. This is where I found Eddie Smith, a local, sitting in a park and playing with a Y-shaped stick resembling a divining rod. I told him I was there looking for water, and there he was, holding the mythic device that is supposed to dip to point to subterranean water flows. He made a joke that he was futilely searching for water only steps away from the Llano River.

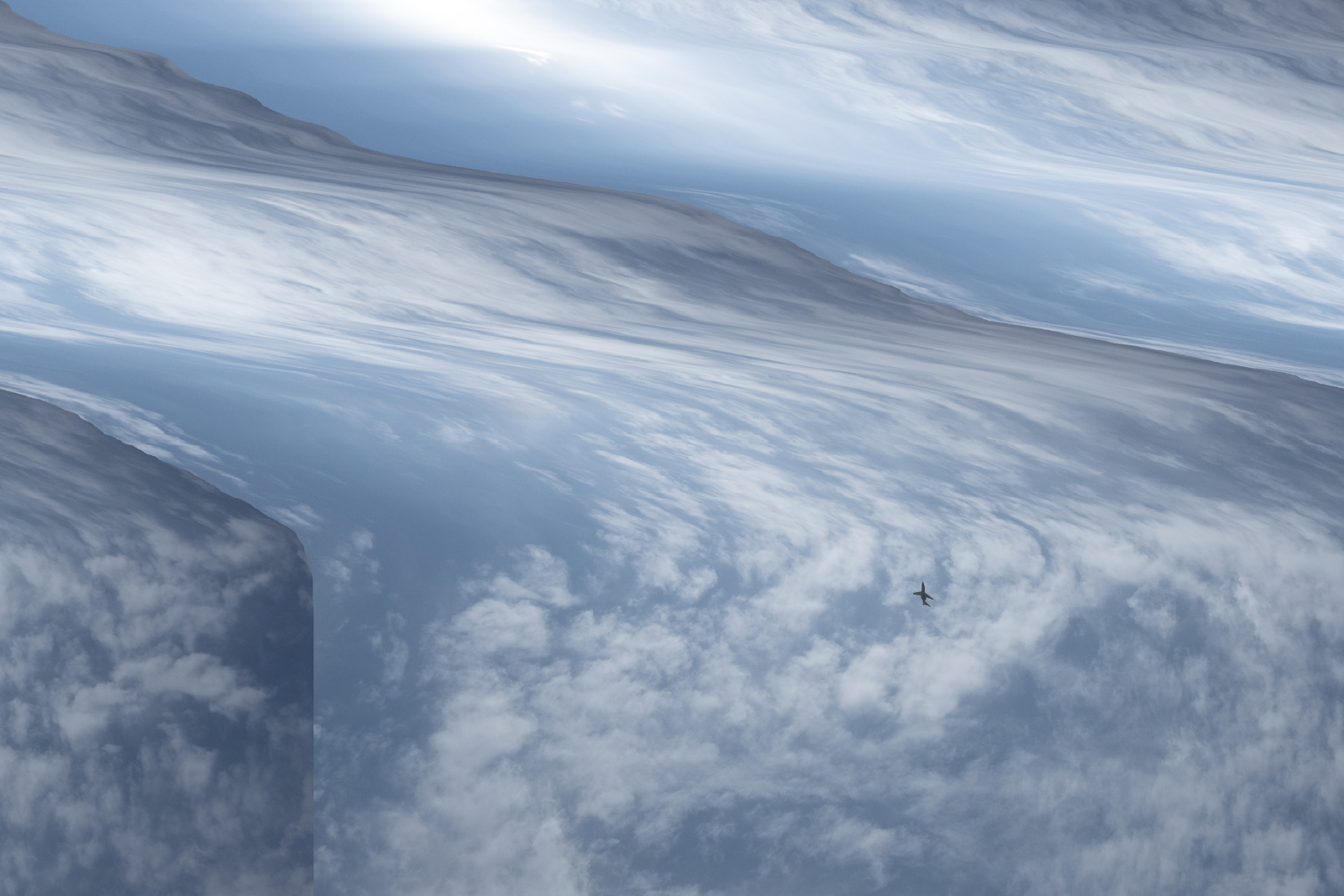

When I visited, Twin Buttes was one of the emptiest reservoirs in the state, sitting at 6 percent of its total capacity—the water in reservoirs in this hot, dry climate evaporates faster than it’s replenished. When I arrived, the park was pretty deserted, save for one large pickup truck parked on the reservoir banks; its owner was there to fish the shallow waters. I found dusty, spent ammunition casings and rusty picnic structures, and the only noise I heard was a menacing roar from a fighter jet overhead, likely launched from the nearby Goodfellow Air Force Base. Curiously, it was threatening to rain by the time I left. The skies darkened and the winds picked up, but not a drop fell.

From there, I ventured into the flat, windy plain of the Panhandle, where both sides of my family are from. In the 1540s, the conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado called this region the Llano Estacado, which translates to the “staked plains.” This territory earned that moniker (so the story goes) because the land was so featureless, Vázquez de Coronado required his men to lay down stakes like breadcrumbs to navigate the uniform terrain.

My grandpa was born in Shallowater in 1913. He was a man of many trades, but family legend has it that, while installing windmills, he noticed he had to dig ever-deeper wells to reach water. He is said to have been one of the first in the area to speak out about the depletion of the water table. I photographed the parched cotton fields of my great-grandparents, which are still farmed today. The wind never stops blowing there. The conquistador’s stakes have been replaced by looming, electricity-generating wind turbines, whose slow, loping blades present the only visual evidence of the air’s movement, against a horizon of perpetual flatness.